books

BEST BEFORE (SEIGENSHA Art Publishing , 2022)

A world of ares and are-nots

Yoshiyuki Okuyama

I’ve had enough already.

For some ten-odd years, the muddle in my head has been getting bigger, the older I get.

And the more I think about all the ares and are-nots, I get so tied up in contradictions that I become unable to make a move.

Humble yet selfish.

Nervous but unaffected.

A worrier and at once a sluggard.

Slow yet impatient.

Greedy, but with a demand for quality.

A confident person who is deeply engrossed in self-denial.

Indeed, I am full of contradictions.

Stuck in the daily quandary between the dictions and the contras, I lean toward the one today and the other tomorrow, and before I knew it, there are things that I am creating while busily running back and forth between the two. After all, that’s what creativity seems to mean in my case: hopping from one extreme to the other and back again.

A mix of reality and fiction.

Consciousness and unconsciousness.

Deliberation and impulse.

Coolness and passion.

Light and shadow.

If there exists a boundary between documentary and fiction, where exactly is it?

While contemplating things like these, I gradually lose sight of my own aims, and of the reason why I am here now.

With no technical skills, no knowledge, no education, not even kindness, I guess it is quite a feat to get this far in the first place.

Driven entirely by the desire to see, shoot, make, and without taking notice of anything or anyone around, I wonder just how many people I have annoyed with my unromantic lifestyle and my rough ways during these fast twelve years… And how many people have come to my own aid!

“Reflect! Reflect upon yourself!”

Well… I don’t actually give a damn!

What I want, plain and simple, is to encounter things that are entirely new to me.

Get drunk with feelings I’ve never known, to the point of suffocation!

Flash! Enwrap! Destroy!

Okay, now calm down.

There are things I need to do first. Sending out invoices for example…

What is important: politeness, earnestness, humility. And a sense of pace.

This is how all the different mes inside myself keep fighting and creating things in the process.

When everything goes well, it’s all good. But when chaos invites more chaos, I feel so troubled and lost that I want to explode, and that is gruelling in its own way.

At the same time, I’m also confident that, when I explode someday, it will blow up those chains of contradiction.

I’m actually quite exhausted already.

But still, I’m going to create something again tomorrow.

For the pure desire to encounter things I’ve never seen before.

To get drunk with unknown feelings.

If possible, I want to keep doing that until I die.

Stuck between the contradictions, between all the ares and the are-nots.

_______________________

Capturing light that never fades – On Yoshiyuki Okuyama’s photographs

Takahiro Ito (curator, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum)

In the summer of 2021, the Taiwanese edition of BACON ICE CREAM was published by Uni-Books. This was in fact the book that introduced the 1991-born photographer Yoshiyuki Okuyama to a broader audience back in 2015, when the PARCO Publishing edition was published in Japan, and the book was subsequently awarded the 47th Photography Prize by Kodansha Ltd.

The Japanese and Taiwanese editions were both published in a similar format (about B5 size), but with vastly different design and architecture that were respectively conceived by Hattori Kazunari and Aaron Nieh – both leading art directors in their own countries. In addition to personal works inspired by daily life situations, the book also contains shots for magazines, advertisements or CD booklets that Okuyama has been doing from the start of his career, and thus covers the entire scope of his wide-ranged work. The numerous images that have acquired a new universal quality once they were removed from the media they were originally published in, highlight the unique stance of Okuyama as a photographer who has been attracting attention in Japan and abroad.

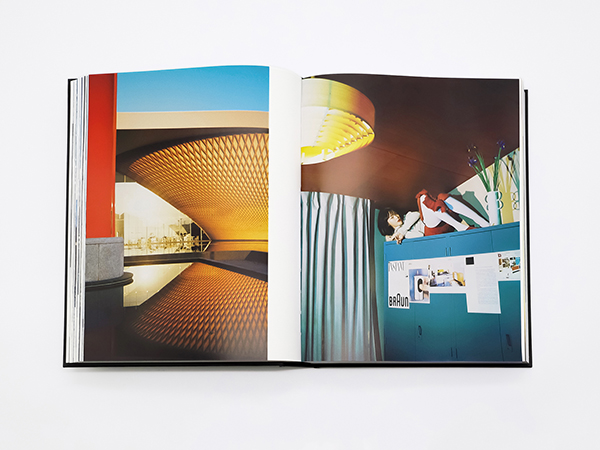

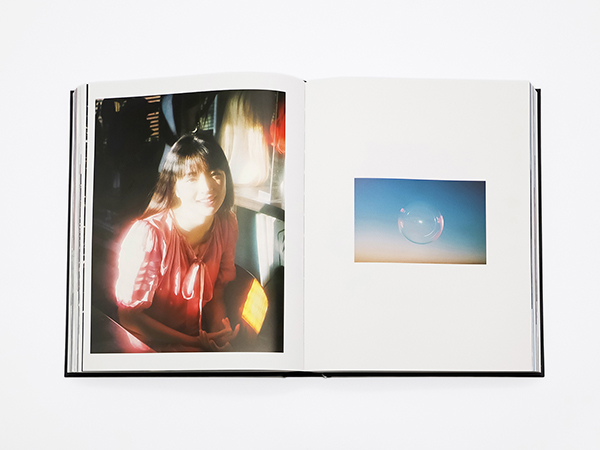

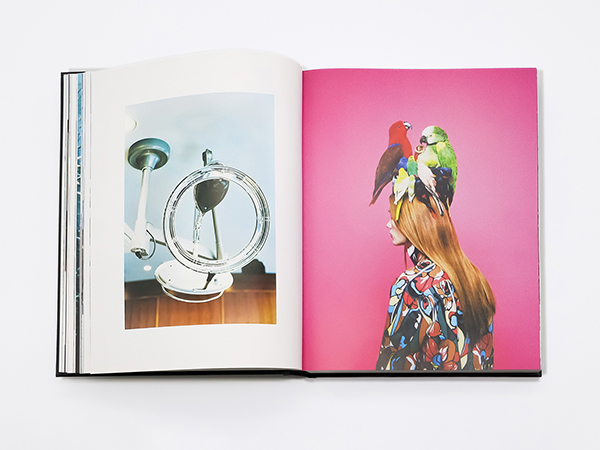

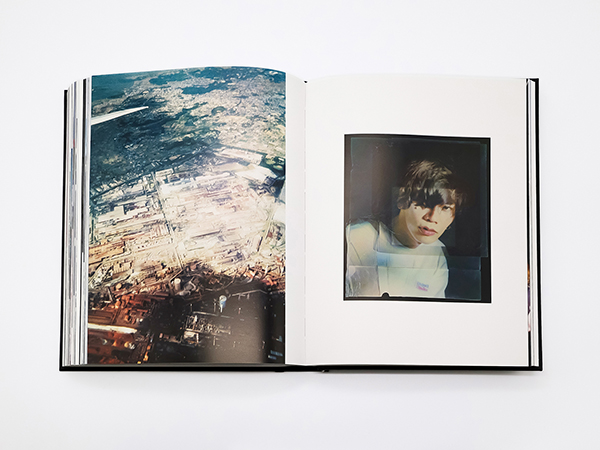

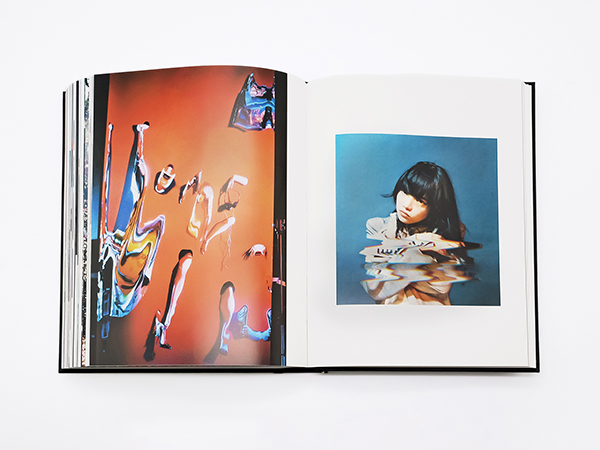

Coming seven years after the publication of BACON ICE CREAM, the somewhat ironically and procovatively titled Best Before collects Okuyama’s works from his early career up to the present. It is a grand compilation of his oeuvre to date, that showcases how Okuyama continues to hone his photographic eye even now, seven years on from his first book. When browsing through the 200+ pages, one of the first things one notices is the high ratio of musicians, actors, models, and other pop icons from Okuyama’s own generation that represent various parts of Japanese culture. They look into the camera while putting on a carefree smile, a funny face, or an earnest expression that is hard to describe in words. What these images communicate is something that goes beyond mere commercial work. It is Okuyama’s profound understanding of the respective cultural area that his models belong to, and the sound relationship of mutual trust that he builds that way.

Contrary to the book’s ironical title, there is a freshness to each of the images contained that won’t easily fade. Come to think of it, from around the time he shot the photos that in 2011 received an Excellence Award at the Canon-hosted “New Cosmos of Photography” exhibition, generally known as a gateway for young photographers, and that were later compiled into Okuyama’s first substantial photo book Girl (PLANCTON), that sense of freshness has always been one of the predominant qualities in his works. The French theorist Roland Barthes wrote the following about the characteristics of the medium of the photograph, an invention from the 19th century, in his well-known book Camera Lucida.

”In Photography I can never deny that the thing has been there. There is a superimposition here: of reality and of the past…”

What Barthes says in a straightforward manner by referring to “things that have been there,” is that every photograph is a trace of the past. While it does happen that this trace is turned into something rather vague over the course of time, in the case of Okuyama, his photographs always remain fresh. It sometimes even seems as though they shine brighter with every day that passes. In the ten years between 2012’s Girl and 2022’s Best Before, which can be understood as one chapter in the photographer’s career, this particular quality hasn’t changed a bit.

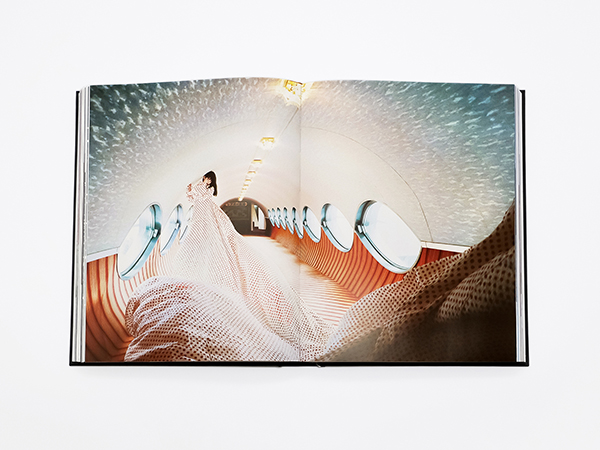

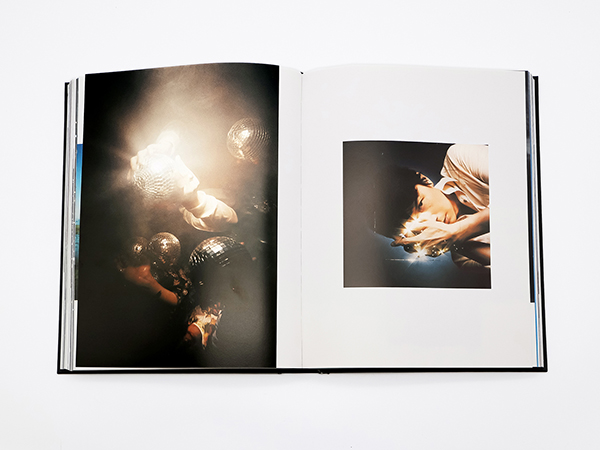

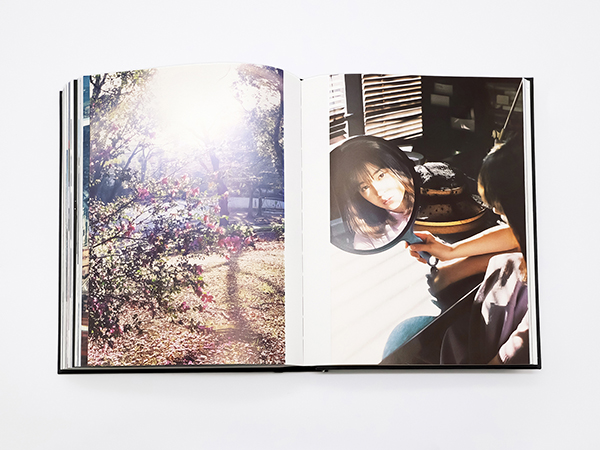

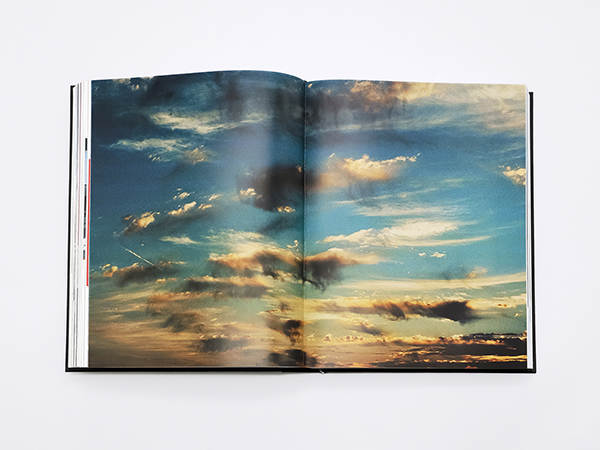

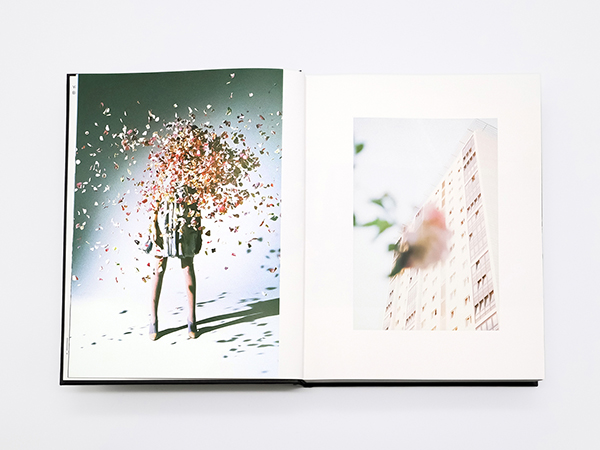

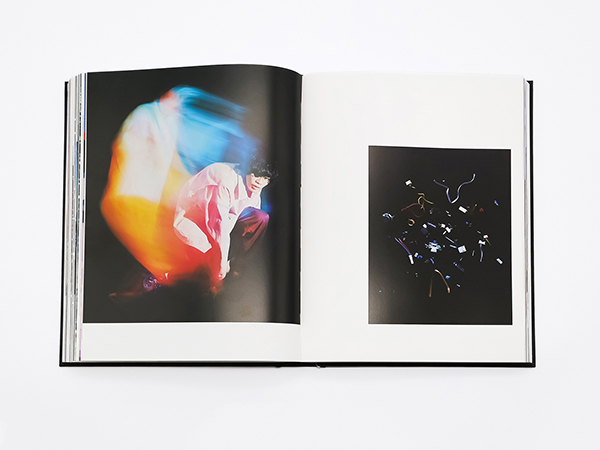

Capturing light that never fades – this is perhaps how one can describe what Okuyama does whenever he shoots a photograph. There are a lot of different types of light contained within the pictures he takes, ranging from dazzling spotlight illuminating a stage, to glittering reflections of the sun in a river, and soft light falling into a room through a lace curtain; from intense, artificially generated light, to faint light as a product of nature. Okuyama observes these different types of light carefully and comprehensively, and catches them all with his film camera in the blink of an eye. In these instant snapshots, the light that has been entched into the film reappear in the form of tiny, colorfully sparkling particles, and the brilliant images that Okuyama produces make us once again aware of the basic fact that a photograph is a medium on which light has been captured.

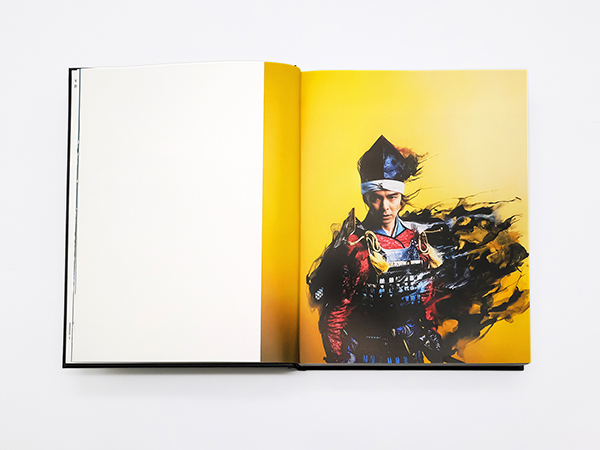

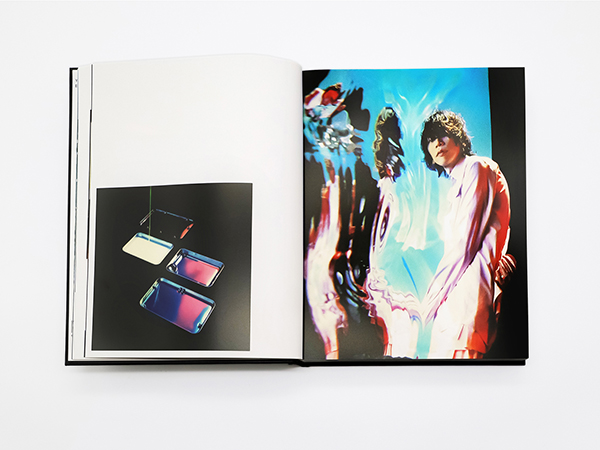

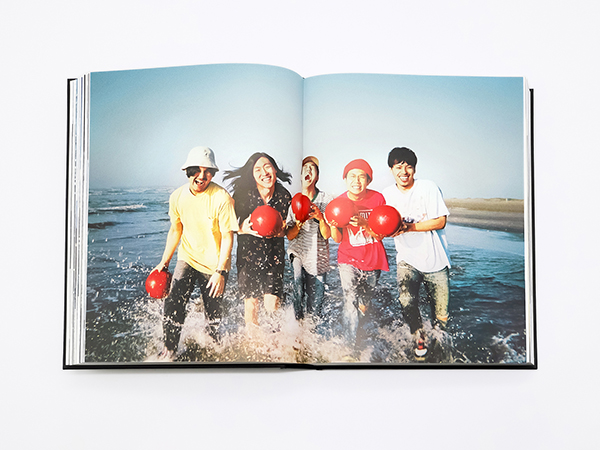

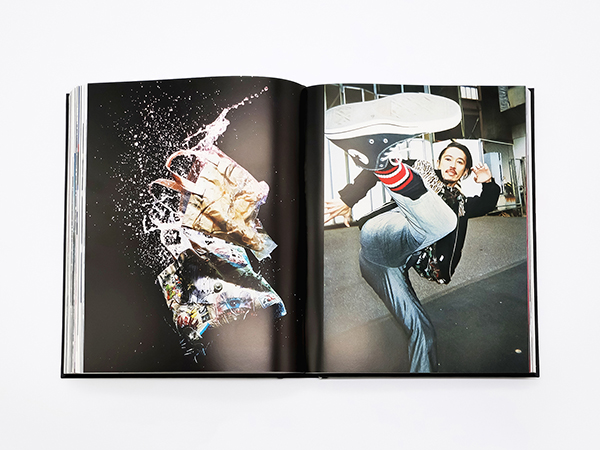

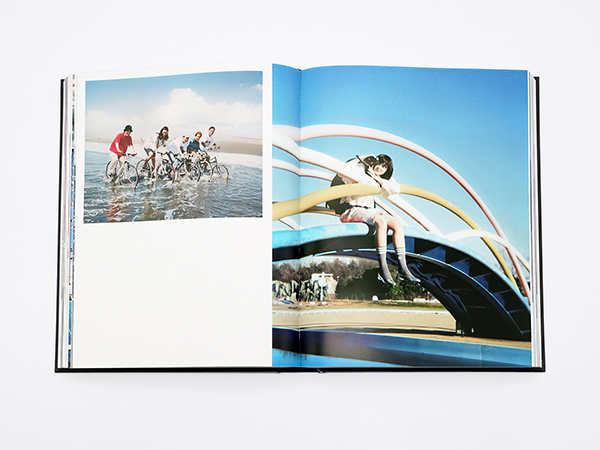

The light that has been etched into the film of these snapshots, contains a variety of human figures. In recent years, the photographer has also been involved in video production, making commercials and music videos among others. Here again, it is Okuyama’s excellent direction style, introducing protagonists into settings of different kinds of light, and thus creating unexpected momentary situations. High school students performing a dynamic dance on a sun-drenched beach; musicians that look as if dressed in cloaks of iridescent light; actors engulfed in diffuse strobe light. These people wear all kinds of facial expressions as they present themselves surrounded by particles of light, and their vivid appearances linger like afterimages even after turning the pages.

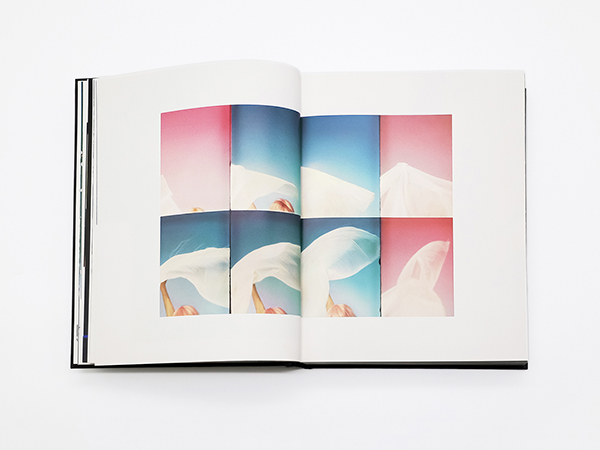

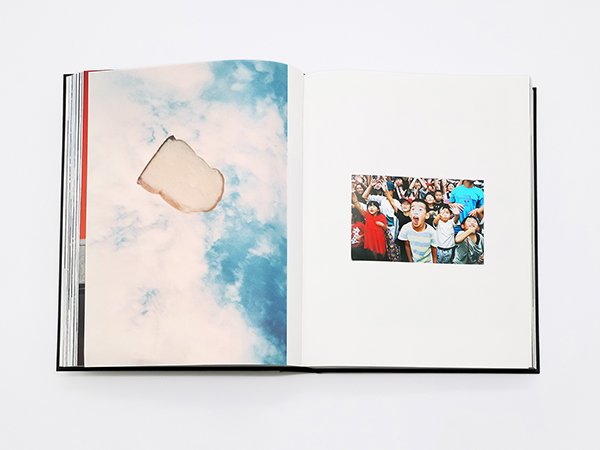

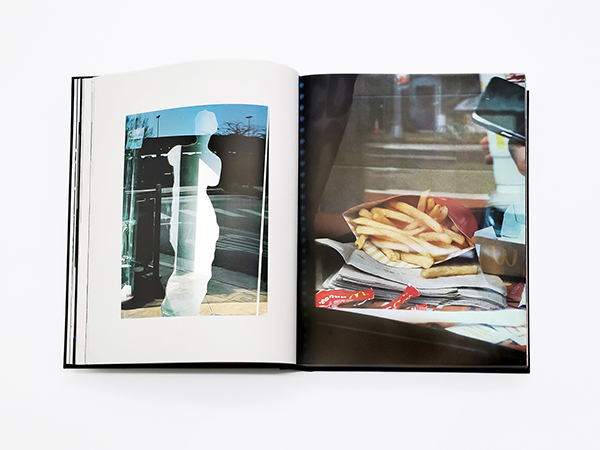

On the other hand, the reader who flips through this book at times also encounters vague, faintly colored silhouettes of flowers; fries and popcorn scattered across the floor of what is supposedly a movie theater; empty wine glasses on a table; and other sceneries that, at a glance, seem like interval signals in the shape of depictions of completely unrelated still objects. In the course of observing these pictures, there are relationships that naturally form between photographs that sit next to each other or on successive pages, connected through common properties such as colors or shapes. And this notion of discursiveness is exactly what makes them so lovely to look at. In retrospect, I remember the cover of the Japanese edition of BACON ICE CREAM being another photo showing a subject as discursive as clouds tinted by the rays of the early evening sun.

The idea that these things evoke in me, is that discursiveness may be one of the essential qualities of photography in general. When people or things come together that aren’t normally likely to meet, that encounter results in the formation of an image. Distinguished photographers who go down in history just “happen” to be there in those moments, with their cameras ready, as if they had anticipated what they were going to witness. What Yoshiyuki Okuyama is particularly skilled at, in addition to just being there, is how he preliminary summons a dazzling light that seems to be waiting at each of his shooting locations.

_______________________

The Magic of Margins – Turning the Everyday into an Illusion

Koichi Kawajiri (editor)

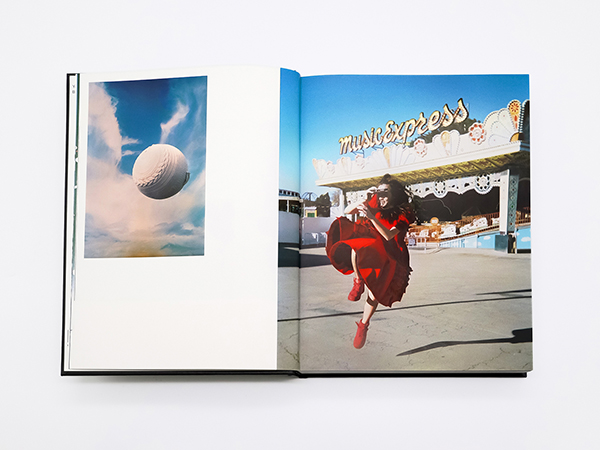

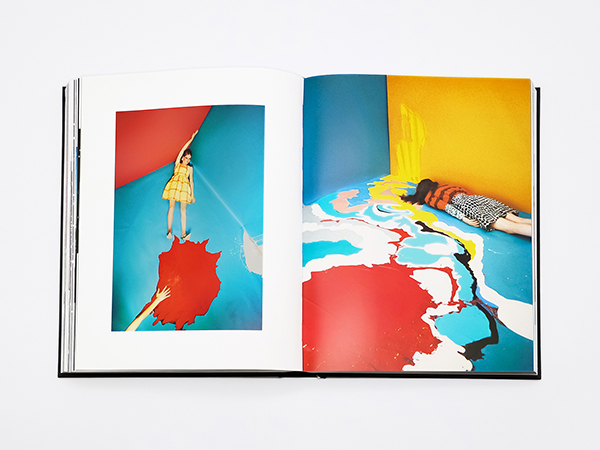

Yoshiyuki Okuyama truly is a magician. At the touch of his hand, even the most commonplace street corner transforms into an unusual kind of place. In the little gaps within ordinary everyday life, he gathers fragments of the extraordinary. The effect is comparable to the illusion of a dove flying off from a while box.

There is plenty of this magic going on in this book, which collects Okuyama’s magazine and advertising work that he was focusing on during the first ten-odd years of his career. It is at once a document that illustrates a certain photographer’s experience of the “ups and downs” of the 2010s.

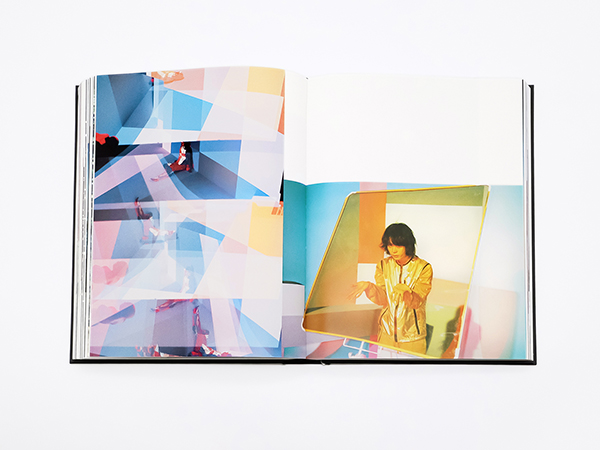

The members of a band enjoy bowling on the beach, while the Taiga drama’s protagonist is clad in armor with an air of ink. Other models are trapped in a maze of mirrors, have their heads wrapped up in cloth, smoke or light, or recline on the grass verge by the wayside. Such oddities of daily life come attached with each of Okuyama’s shots.

For this photographer, every hour of the day seems to be a golden hour.

Arranging and presenting all kinds of subjects as instant ”performers” is Okuyama’s forte. In addition to actors, artists, and other professionals in “being photographed,” there are also ordinary people such as members of high school dance teams, children or fishermen, and even objects like bread, food packages or dishes, that (appear to) act in Okuyama’s little plays.

What makes it all so very strange is the fact that every photograph looks perfectly “normal,” goes down just like water. It preserves the photographer’s mind and consciousness, and his message, in an almost stoical manner. Simply speaking, there is no bragging, no showiness. The behavior of the people and things in these pictures seems just perfectly natural.

And this is what makes the viewer believe. We believe that this is not an illusion fabricated by a creator, but a moment within real life. A bit like when we believe a magician who asserts that “there’s no smoke and no mirrors.” To some people, the photos may look like random snapshots taken at a whim.

This, however, isn’t at all true. Okuyama’s magic is full of smoke and mirrors, and every single one of them is arranged with a degree of meticulousness that borders on the excessive.

In the space that functions as his atelier, all sorts of cameras and other gear, as well as various props that he uses for shooting, are stored in a super-orderly fashion. Large amounts of negative film and “Utsurun-desu” (disposable cameras) are sitting in the fridge waiting for their turn. Okuyama explains this extreme orderliness with the fact that this gives him quicker access to his archive, which in turn inspires more ideas.

As I don’t want to reveal too much about his tricks, I won’t go into detail here, but many of the props are things that one doesn’t normally encounter at photo shootings. According to the photographer, they are tools to make his subjects move, and that bring out their subconscious mind.

Okuyama concentrates his efforts on preliminary preparations, as if his life depended on the ”slight differences” that energe as a result. The voids generated by these ”slight differences” is where he senses the presence of passion. There is something that isn’t quite normal even though it appears normal. Something extraordinary that oozes out from the gaps in the ordinary. In order to illustrates such paradoxes, Okuyama spares no effort in his inspections.

It is said that a first-class magician precisely calculates every single action in every single moment of his stage show, and this is also how Okuyama goes about his work. He is a shy looking but tough acting photographer.

Being at once also a video director (which he has in fact been doing longer than photographing), Okuyama previously explained in a number of interviews how photographs are for him like “dots” while movies are “lines.” Rather than still pictures, he seems to be more concerned about “moving” or “transforming” ones. The work of a photographer he describes as “looking for dots that eventually become a line.”

The myriad “dots” he has amassed that way, he examines closely one by one, apparently rejecting those cuts that seem perfect as “dots.” Okuyama’s photographs are all about the dots that leave enough room for the viewer to imagine the “lines” they may form.

In other words, creating a photograph is for Okuyama a combination of “releasing the shutter” (the field-work) and “selecting” (the atelier work). The “shooting” is a continuous operation, from the initial preparations to the final selection, which in some cases includes duplicating or processing the resulting images. It is through this entire process that Okuyama’s magic is accomplished.

Many of those who look at his photographs detect in them a movie-like emotive quality – something that can make people rhapsodize or shudder for example. This must also be what lends the images a very human kind of texture, regardless of their rather cool first impression.

In that sense, there is a very contemporary quality in Okuyama’s work, while at once also representing an artistic attitude of timeless validity. The Kabuki and Joruri artist Monzaemon Chikamatsu is said to have stated that “the appeal of art lies in the slender margin between the real and the unreal.” The truth of art exists in the very space between true and false, and this may be just what he practices, simply and honestly.

Let me go a step further, and say that Yoshiyuki Okuyama is at once a visual hacker.

In a society that is flooded with all sorts of information and contents, it isn’t easy to create something that touches people’s hearts. In order to cut a figure not only in the realm of IT, but also in art, economics, and any other field, it takes something like a hacker’s ability to sneak into the gaps of the times.

Hackers are always on the lookout for new ideas and methods, and they never use the same trick twice. This applies also to Okuyama. For each of his works, he can minutely illustrate the respective method that he tried out, in a way a developer would explain a programming code.

Okuyama’s hacking nature at times reveals itself rather intensely in the videos he directs.

Take the music video for Kenshi Yonezu’s song ”Kanden” (2020) for example. In this video, Okuyama uses the various glass surfaces of a car as ”screens,” and by deliberately blurring he boundary between inside and outside, he cleverly visualizes the artist’s shaking self-image.

The idea of using the car’s windows and mirrors as frames is quite interesting. The minutely complex camera work with split-second cuts reportedly is a result of scrupulous rehearsals with cameraman Kawakami Tomoyuki and the production team.

The approach Okuyama tried out for “Owakare no uta” by never young beach (2016) can be described as hacking the song by way of a documentary style video. Okuyama made a movie in which a man recounts his memories of days spent with his girlfriend, and subsequently added music to it, whereas the song this was made for in the first place doesn’t start until halfway through the video of seven minutes and thirty seconds length.

The vertical format, making it look as if shot with a smartphone, was another element that broke all rules in the world of music videos at the time. In order to make the result come across as real as possible, Okuyama did various research, such as asking several friends to show him videos and photos of personal memories.

Yoshiyuki Okuyama is at once a magician and a hacker.

Old-fashioned craftsmanship that demands flawless manufacture, and modern sensitivity that lightly topples common sense and existing frameworks. Here is one artist in which these supposedly conflicting characteristics come together as a natural, hybrid kind of quality.

Photography and video, ordinary and extraordinary, private and commissioned work, cool and passionate – I guess this motion, going back and forth between the extremes like a pendulum, is the very source that Okuyama draws his power from.

As a creator who strives for “transformation,” Okuyama will probably continue to update his work. For someone who is always on the move, there is no ”best before.”