exhibitions

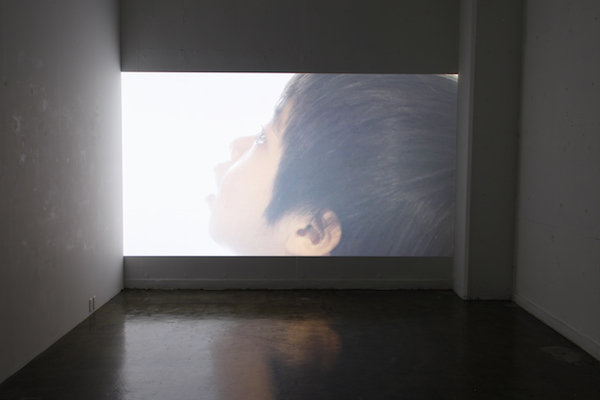

As the Call, So the Echo (Gallery 916 , Tokyo , 2017)

As the Call, So the Echo

Yoshiyuki Okuyama

Not sure when it was that, in a book I happened to open, my eye fell upon that piece of text: “As the call, so the echo.”

Murmuring it aloud to gauge how it sounded, I found I also liked the intonation, and the resonance, so chose it for the title I had been struggling with.

Be it words or attitude, the elements people send out always come back to them eventually, like a ball thrown against a wall. The good, and the bad.

In the past few years this fact has been brought home to me by many things that have happened, and I’ve begun to wonder if the surrounding environment, which forms in the manner one might draw a sphere, has a shape determined by “something” we emit ourselves. In addition to the likes of verbal exchanges, and actual physical contact, people seem to communicate via a mysterious “something.” A thing slightly different to aura, mood, ambiance. A sensate thing that defies exact description, and which thus I am compelled to classify, for the time being, by the overly broad term “something.”

That “something” can often be found in photographs.

Keep your eyes peeled and your ears open, and just look for a while.

You’ll find colors that are not colors, hear sounds that are not quite sounds.

And, just like an echo, a moment will come when you will hear it.

Not a thing with sound waves – leaves rustling on trees, the mewing of a cat, the sound of guitar playing, children frolicking, that kind of thing – but sounds never audible while clicking the shutter. Sounds first heard on looking back at the print. Relying on that undulation, that air of something quivering and shimmering, a wave motion, I arrange the photos.

Some years ago, having put together the Bacon Ice Cream photo collection, I suddenly found myself unable to hear those sounds. Everything I saw looked gray.

A sound that made it to my ears, but not all the way to my brain. Though visually they must have been visible, mentally I could no longer see colors.

That sensation, a first for me, alerted me to the existence of a presence that could be interpreted as both color and sound. That is, I learned that when it comes to photographs, color and sound are equally significant.

Picking up the camera for the first time in a while, and taking photos in a location far from Tokyo, it struck me the resulting shots brimmed with kindness, and were free of the introverted quality that comes from looking at myself. There was a sensation of keeping my gaze firmly on the people in front of me, and engaging head on, without any awkwardness.

I was delighted.

Delighted to note that the “something” I had identified in the everyday we take for granted had turned out to be a thing very close to kindness, and to have noticed, as well as a positive joy, the invisible presence possessed by these photos.

This work in four sections is composed of photos documenting the Nagano village home to my friend Tetsuro and his family, events at the pool he built, and a little show at the Kichimu event space in Kichijoji. The first time I met Tetsuro, he was walking toward me in bare feet along a path rendered squelchily swampy by heavy rain, but still managed to greet me with a smile. His presence as sensed on that occasion was of a color clearer and purer than I had seen in anyone before, and sure enough, people flocked to him as if drawn in by its sound. That environment looked to me like a very soft sort of sphere, and unmistakably, it was their way of life that revived the presence in photos that at some point had stopped.

Hopefully the folks in the village are well.

I wonder how they will work in concert next, what kind of sphere they will create.

_______________________

Toward a lived now

Mariko Takeuchi (Critic)

What exactly do we mean by now?

That which gives us a sense of now. That which seems to be of now. In every era, these tend to be received positively, because they make us conscious of ourselves as beings living through the same times, and let us feel that we are sharing something. Perfect proof of this may be found in the millions of “liked” photos on social media. The key words are sense, and sensibility. Perhaps we can refer to this variety of now as “now as imagery.” That is, now as what one might call collective fantasy.

This “now as imagery” is ephemeral, and highly mutable; no more than something divorced from the past, with the presentiment of a promising future. Which is why however, it intoxicates us and even if just for a moment, allows us to forget the isolation of being alone. Even, perhaps, forget a past hard to forget. The “now as imagery” thus made a device for our desires joins hands with consumerist culture, infesting every aspect of daily life, escapable by none.

Yoshiyuki Okuyama debuted as a photographer in 2011. His maiden work Girl was suffused with a tranquil, transient quality reminiscent of cuts from a 8mm short film. Characterized by the repeated appearance of a hazy female figure, its curtain by a wall, and the detail of the sheets, seem to flutter between dream and reality, the sweetness of being alone when faced with the gap between oneself, and someone almost but not quite able to be reached, hanging about the images along with a vague whiff of madness.

Once out into the world, these introverted, naive images embodied in the work of a youth on the verge of twenty were an instant hit. Now finding himself fielding a flood of offers, with his innate sincerity and dexterity, Okuyama responded the best he could. Yet amid this undeniable success, perhaps he gradually became bewildered by the way his photos were only being consumed in the “now as imagery,” because where they arose from was a much smaller world, a surprisingly frail and easily wounded world, far removed from such collective fantasy. Although one could say it was that very frailty that had proven so seductive.

The photo-collection As the Call, So the Echo appears to find Okuyama pausing for a while, a little over six years on from his debut, to reaffirm each individual innate link between living and photographing that he was on the verge of losing. Both living and taking photos can only be in the here and now in the first place. It is utterly impossible to live or photograph any “sometime” or “someplace” other than the point in which we thus stand. Which is why he searched for a now different from “now as imagery”; a now not as fantasy divorced from past and future, but a “lived now” hand in hand with past and future.

Across the globe and throughout the ages, for the very reason that people can only live now, they have looked to the traces of a cumulative past to learn, in the now, what makes human beings human, taken on the knowledge possessed by their ancestors, and pondered the proper path. In my view, by nature the job of not only the photographer, but also the artist, is something akin to this. Rejecting uncritically toying with “now as imagery” to quietly question the state of such timeless fantasies, then having done so, positing to the now little questions directed at the future: this requires, before any question of sense or sensibility, a fundamental intelligence and humanity that endeavor to learn from the past. At the risk of being misunderstood, I would describe this quality as modesty in the face of history and nature, as opposed to facile self-affirmation or the like.

It strikes me in a sense inevitable that the friend who guided this work in substantive terms was someone who moved from Tokyo to Nagano, and makes things amid nature while enjoying loose, easy connections to the people around him. Okuyama clicked the shutter tirelessly, capturing the day-to-day scenes playing out there with the fresh amazement of someone seeing people on the earth for the first time. Okuyama himself also notes that here he wanted not so much to take photos as to press the shutter, that is, rather than taking photos to realize what those around him required, simply respond honestly to what he saw, and click the shutter as naturally as breathing. Then, once the shoot was over, contemplate the meaning of these photographs at his leisure. This, he says, was his desire.

So where did the photographs shot in this way take the photographer?

A hint is in the title, the idea of one’s own call returning as an echo. It could also be read as this world we see now, ultimately being one that we called to us. Thus does the world reflect me, and I reflect the world while living in it. In the resonance between them, with no beginning or end, past and present and future mix, and you and I will definitely meet.

Incidentally the word echo has its origins in the wood nymph Echo of Greek myth. Blaming Echo’s chattering for her own inability to catch her husband Zeus in his dalliances, the god’s wife Hera cursed the nymph to only repeat the words of others. The echo is her voice. Intriguingly, in Japanese too, echo (kodama) is written with the characters for wood nymph. The way voices and sounds are heard reflected back with a delay in mountains and valleys was believed to be the work of spirits residing in the trees. Perhaps people once sensed, in the resonance between themselves and the world, not merely a one-to-one relationship, but a circuit connecting them to a much larger, invisible, all-embracing presence.

Perhaps too, in this unmistakable presentiment of connection to something greater than ourselves, the sweetness of being alone is supplanted by delight in the tiny miracle of simply exchanging our gaze with someone else. Ears tuned to the reverberations of such subtle echoes, Okuyama stands at the gateway to a “lived now.”